Four Square Miles of Carboniferous Forest Discovered

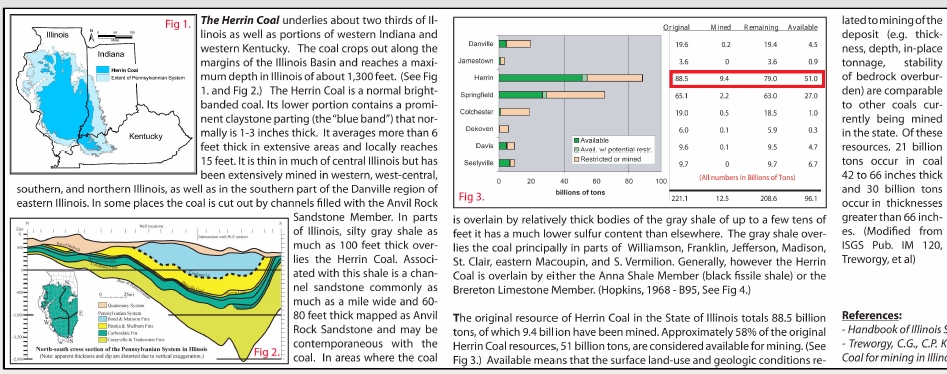

Smithsonian paleontologist Bill DiMichele and colleagues Howard Falcon-Lang (University of Bristol), John Nelson and Scott Elrick (Illinois State Geological Survey), and Phil Ames (Peabody Coal Company) discovered the remains of one of the world's oldest tropical rainforests, preserved in the ceiling of a coal mine 250 feet below the surface. Their discovery was recently published in the journal "Geology" entitled "Ecological Gradients Within a Pennsylvanian Mire Forest."

The rainforest extends over more than four square miles as the roof of two adjacent underground coal mines in eastern Illinois. This may be the largest single-time-period fossil forest found in the fossil record.

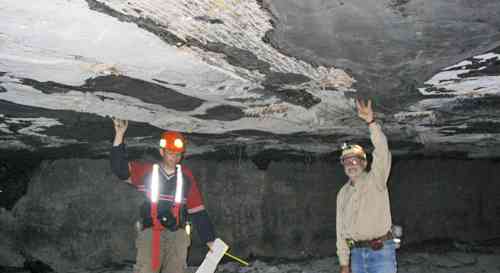

Fallen trunk section. A section of a large trunk has fallen from the roof and lies in the middle of the floor, to the right of the backpack. In the background, study coauthors John Nelson and Howard Falcon-Lang are examining the roof for plant fossils. The sides of the room are the coal bed.

A forest of lycopsid trees and tree ferns was uniformly developed throughout this area, and an understory of horsetails, seed ferns, and cordaitaleans (seed plants related to conifers) filled in under and around the tree fern-lycopsid forest where the land was drier. The forest was preserved when an earthquake dropped the area a few feet allowing flooding from an adjacent river, which drowned the vegetation and buried it in sediment. The sudden flooding in the submerged block killed the rainforest. Mud and silt rushed into the depression, preserving the stumps and logs in a layer that eventually became shale.

Neuropteris, part of a frond of a "seed fern", seen on the mine ceiling or roof. The roof is the forest floor of the swampy environment in which these plants were living. Miners removed the coal bed exposing the forest floor "this would be the worm's eye view" (if worms had eyes!). Seed ferns were seed-bearing plants that had large, highly compound leaves much like ferns (hence their descriptive name).

Plant

fossils are common in coal beds. Coal is the compacted result of peaty

plant material. These are the remnants of extinct plants from

Carboniferous period 300 million years ago, when the world was covered

in lush, green vegetation. Illinois was near the equator and much

warmer and wetter.

The forest's animal life was also unlike any found today, it was the age of insects.

Early amphibians,

dragonflies the size of seagulls, and nine-foot-long (three-meter-long)

millipedes roamed the now lost world, the scientists said. But no fossils of these lost animals remain, according to Elrick.

"We only saw a few insect parts," he said.

Howard Falcon-Lang and John Nelson are standing on opposite sides of a large, prostrate trunk of a giant lycopsid tree. This monster tree is over 6 feet wide and stretches for over 120 feet, neither the base nor the top can be seen.

Giant tree ferns would have formed a lower canopy 30 feet high. Poking up through the ferns would have been 100-foot-tall clubmosses , asparagus-like poles that sprouted crowns full of spores. "What's extraordinary about this discovery is that this forest has been preserved in its growth position," said Falcon-Lang. "It's an upright forest with trees still standing upright."

Base of lycopsid tree stump buried while still upright, as seen from underneath. A metal plate keeps the stump from falling and injuring the miners. The trunk projects up into the roof shale. This stump would have been "rooted" in the very top of the coal bed.

Lead study author Bill DiMichele said the lateral extent of the fossils allowed him to notice subtle changes in species diversity as he did surveys. As mining continues, the size of the exposed fossil forest grows by the day. DiMichele is now doing inventories of ancient plants in two other actively mined Illinois coal seams, the Danville and the Springfield, which sit above and below the Herrin, respectively, and are separated by about a half-million years of geological time. Where most botanists do their work by walking through a forest, DiMichele takes elevators down mine shafts "to get beneath the forest. "We get to walk under it and look up at it," he said. "It's the earthworm's view."

Pith cast of Calamites, an extinct sphenopsid, but a close relative of the modern horsetails (Equisetum). Note the nodes (lines around the stem) where leaves and leaf-bearing branches would have been attached.

Coal-swamp reconstruction: Peat forming swamps, also known as "mires", formed over vast parts of what is now the eastern United States and Western Europe during the later Carboniferous Period. The coal beds of these regions are the remains of these swampy landscapes. This reconstruction, done by Mary Parrish of the Department of Paleobiology, shows a forest dominated by a mixture of lycopsid trees (front right, also with juvenile tree), tree ferns (center front, with "mantles" of prop roots extending out from the trunks), seed ferns (left center, short trees with crown of frond-like leaves), and calamites (right side rear foreground, with branches in whorls). The forest is open and includes many vines and low-growing plants.

Above ground, showing the flat, central Illinois landscape near the Riola mine, 250 feet above the coal seam. The current landscape is a far cry from the rainforest vegetation of the Carboniferous Era, 300 million years ago.

More photos and detailed information about this study can be found at the Illinois State Geological Survey ( click here ), or online at http://www.isgs.uiuc.edu/research/coal/fossil-forest/fossil-forest.shtml.

© Copyright 2007 Smithsonian Institution